Carbon in the Caribbean Part I: The Global Carbon Economy

This article is the first installment in a three-part series exploring the Caribbean’s developing relationship with carbon markets. Part I provides an overview of global carbon markets and situates the region within the broader global carbon economy. Part II unpacks the contributing factors behind the region’s limited participation in carbon markets to date, and Part III explores solutions and pathways for building a viable carbon economy in the Caribbean.

As environmental sustainability has risen to the forefront of the global agenda, climate innovations have surged alongside it, spawning new technologies, industries, and markets. Among these, carbon markets have emerged as a central mechanism for driving emissions reductions and mobilizing climate finance, influencing corporate strategy, shaping national climate policies, and increasingly determining which countries and regions attract investment for mitigation and resilience.

This article provides an overview of how carbon markets function, the scale of the global carbon economy, and the benefits it can deliver, setting the stage for a closer examination of one of the most underrepresented yet climate-exposed regions in this space: the Caribbean.

What are Carbon Markets?

Carbon markets are financial mechanisms that assign a monetary value to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in order to incentivize their reduction. They operate on the principle that if polluting becomes costly, efforts to reduce emissions become more financially attractive and more likely to be implemented.

These markets facilitate the trading of carbon credits, each representing one metric ton of CO2 or its equivalent reduced, avoided, or removed from the atmosphere through verified climate initiatives.

| Project Type | Carbon Impact | Common Activities |

|---|---|---|

| Avoidance | Prevents release of new emissions |

|

|

Removal |

Extracts existing emissions from atmosphere |

|

| Reduction | Decreases the amount of emissions released, compared to what would have happened otherwise |

|

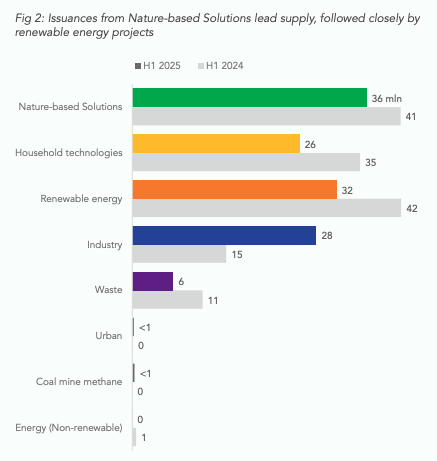

Such initiatives range from nature-based activities to technology-based solutions, although nature-based solutions (NbS) notably account for a more substantial share of global credit issuance.

Despite mainly targeting large emitters like corporations and countries (i.e., governments), the system involves a diverse ecosystem of actors including project developers, financial intermediaries, verification bodies, and standard-setting organizations, all interacting within a structured system of credit issuance and trading according to set credibility criteria around emissions reductions claims.

By turning emissions reduction efforts into something measurable, valuable, and tradable, carbon markets: align financial incentives with climate goals; enhance accountability and transparency around climate impact; enable faster and more cost-effective climate action pathways; and mobilize capital flow towards climate-positive projects, often supporting smaller or less financially resourced emitters.

The Global Carbon Economy

Over the past decade, carbon markets have evolved from a niche policy experiment into one of the most widely adopted economic instruments for climate action. Today, the global carbon economy runs on a dual-engine system: a rapidly expanding Compliance Carbon Market (CCM) driven by national policy and regulation, and a relatively mature yet ever evolving Voluntary Carbon Market (VCM) driven by corporate decarbonization commitments and private investment. Working in conjunction to capture the world’s largest sources of emissions, these markets have become a central, and increasingly unavoidable pillar of the global decarbonization strategy.

As of 2025, direct carbon pricing instruments cover about 28% of global greenhouse gas emissions and have generated over US$100 billion annually for public budgets for the second year in a row. In parallel with driving emissions reductions, market activity has simultaneously supported efforts of environmental damage reversal and ecosystem recovery. The VCM in particular has played an outsized role in innovation and the proliferation of natural climate solutions, supporting a wide range of project types across diverse geographic settings. In 2024, it mobilized US$16.3 billion in new funding, with nature-based initiatives consistently representing at least one-third of all carbon credits issued in the market.

As carbon markets mature, financial sophistication is accelerating with more complex financial products and investment structures, greater participation by institutional investors, stronger standardization, and integration with broader climate finance frameworks. Combining the trading volumes on compliance and voluntary schemes, estimates valued the global market anywhere between US$850 billion and US$1.14 trillion in 2024, with optimistic forecasts suggesting it could reach US$2.7 trillion by 2028 and climb further to US$22 trillion as we approach the 2050 net zero target staged by the Paris Agreement.

This trajectory is supported by a number of reinforcing factors, including:

Anticipated expansion of compliance systems: Major economies are tightening their carbon pricing regimes, expanding emissions trading systems, and integrating carbon costs into broader industrial and trade policy.

Rising corporate participation: Today, over 40% of global market capitalization is engaged in setting or pursuing validated climate targets, an important driver of voluntary market demand.

Rising carbon prices: Pricing in both compliance and voluntary schemes are projected to increase amid shrinking decarbonization windows, scarce credit supply, and high-integrity demand.

Scaling of carbon removal technologies: Breakthroughs in advanced, largely tech-based carbon removals are expected to expand supply at high prices, working alongside traditional nature based solutions to combat residual emissions.

Integration with Article 6 of the Paris Agreement: 102 bilateral agreements are now in place between 62 countries under Article 6.2 of the Paris Agreement to enable cross-border carbon credit transfers, connecting high emitters with high potential credit supply, creating new demand from governments and supporting higher-value credits with stronger integrity.

Together, these developments signal the rise of carbon markets as a central conduit for global climate finance. And while not without its challenges, this evolution underscores their growing role as a foundational asset of the global net-zero economy—now embedded in economic planning and corporate strategy, and left to increasingly shape wider international trade, investment, and climate action progress.

Benefits of Carbon Market Participation

Participation in carbon markets offers much more than emissions reductions, unlocking broader advantages for sustainable development through added social, environmental and economic co-benefits built into carbon projects, such as biodiversity protection, improved health, local education and cultural preservation. By design (and in theory), these market-based mechanisms channel actions towards solutions that create value for all participants, creating opportunities to align multiple priorities and respond flexibly to the diverse interests of stakeholders.

For companies, they create a practical, scalable, and cost-effective way to finance decarbonization and support credible net-zero transitions.

For local communities, they can be a means of infrastructure development, capacity building, improved ecosystem services that reduce community vulnerability, and improved livelihoods.

For governments, they can facilitate progress towards multiple policy objectives, channeling investment into industrial improvements and nature and resilience to meet nationally determined climate commitments and support local development. Over half of the funds raised by carbon pricing for public budgets has been reinvested locally into environmental, infrastructure, and development projects.

In this sense, carbon markets act as a convergence point for environmental integrity, economic opportunity, and development priorities, providing not only a mitigation instrument for countries and organizations with substantial carbon footprints but also a tangible route for nations and communities that are simultaneously climate-vulnerable and capital-constrained.

Opening Development Pathways

At least 90% of carbon projects active globally are developed in the Global South, largely mirroring its abundance of mitigation assets, particularly nature-based solutions. This concentration of project potential has placed developing nations at the heart of global carbon market supply, positioning these countries to benefit directly from market participation.

For many developing nations, carbon credit trade provides a viable route to access climate finance at scale, mobilizing the resources and development of systems and initiatives needed to adapt, grow sustainably, and chart their own climate-resilient pathways. As the global carbon economy expands, the opportunity for these nations to leverage their natural assets for sustained, sovereign climate financing becomes not only plausible but increasingly central to the story of global climate justice. Key benefits include:

Unlocking new, dependable avenues for climate finance: Carbon markets are one of the few decentralized climate finance mechanisms that bypass large multilateral processes. Unlike traditional climate finance, which is often tied to donor priorities, external aid cycles and/or political negotiation, carbon markets create a more predictable and steady flow of revenue linked to natural assets and verifiable mitigation outcomes.

Building resilience through adaptation co‑benefits: While carbon markets are framed around mitigation, many participating projects deliver strong adaptation and resilience outcomes, impacts which are especially pronounced in climate-vulnerable developing states. These outcomes are critical for strengthening local capacity and rural enterprise, safeguarding livelihoods, and enhancing overall quality of life. For example, improved cookstove projects reduce emissions while improving air quality, cutting fuel use, and slowing deforestation, which in turn contribute to healthier, more resilient communities. Similarly, blue carbon initiatives (e.g., mangrove restoration) can finance early‑warning systems, coastal protection, or other resilience infrastructure, delivering both environmental and social benefits, particularly in countries, such as island states, where economic activity and livelihoods are closely tied to coastal ecosystems.

Strengthening sovereignty and long-term development: The process of developing and managing carbon projects strengthens monitoring, land-use governance, environmental policy capacity, technical capacity, and global credibility – benefits that often extend beyond the projects themselves. At the societal level, carbon initiatives can reinforce land rights, empower local communities through participation and benefit-sharing, and create jobs and skills. For countries rich in ecosystems but limited in fiscal space, they also enable new financial autonomy in a climate finance system where they have historically had little bargaining power, unlocking value that has always existed in developing countries’ ecosystems, but was never previously monetized on their own terms. In this sense, countries and communities gain a meaningful measure of self-determination in climate action, reducing dependence on donor-driven finance, building state capacity, and taking agency in their climate agendas.

Underrepresented Regions in Global Carbon Markets: The Case of the Caribbean

Still, while many countries have been able to tap into the opportunities of the global carbon market, some nations’ roles remain underexplored, particularly Small Island Developing States (SIDS). Despite high climate vulnerability and notable natural ecosystems, Caribbean participation in particular remains fragmented and undercapitalized.

Environmental Context

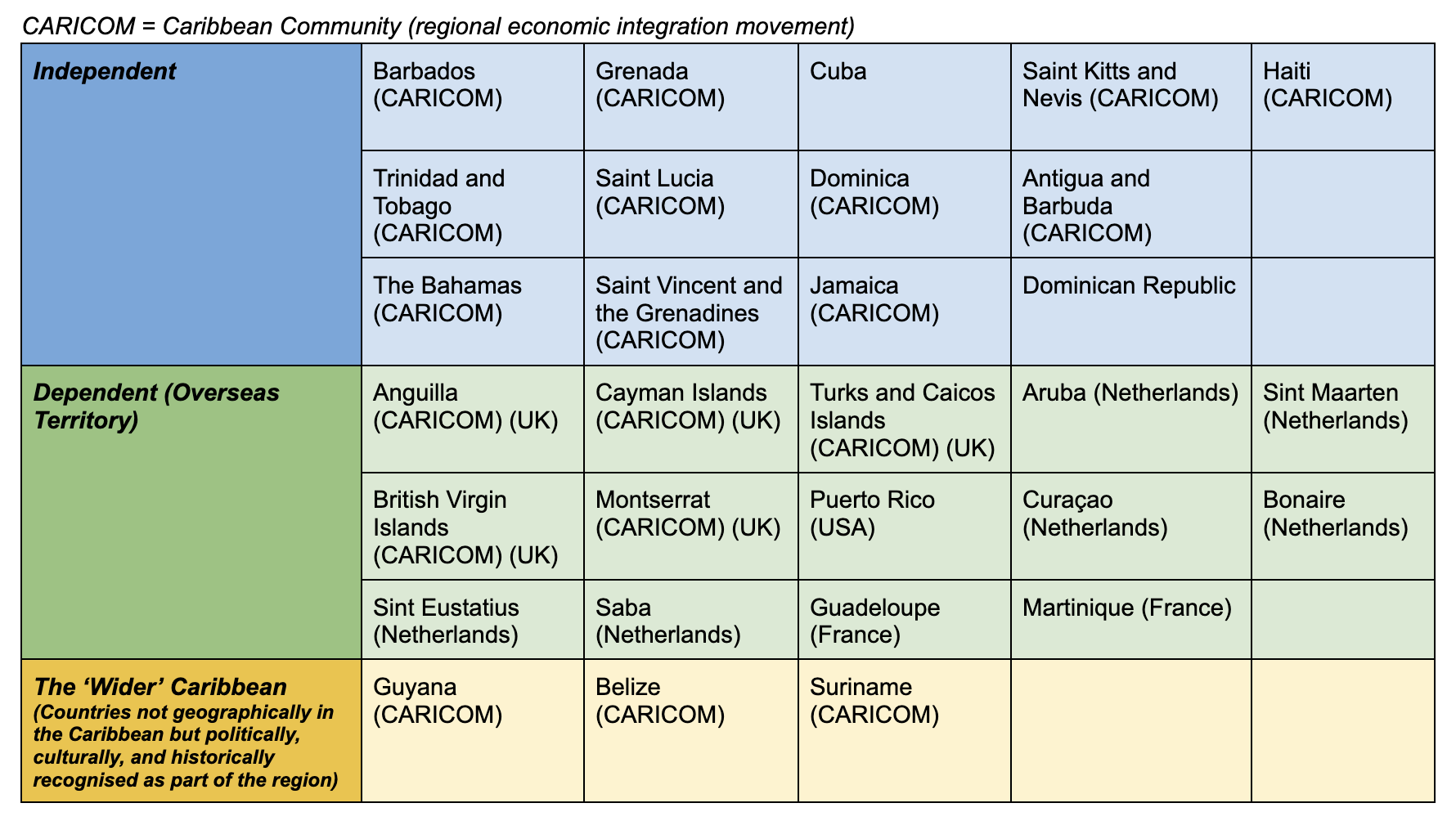

The Caribbean comprises roughly 30 countries – 13 sovereign states, 14 overseas territories, and 3 continental states – each with distinct environmental and economic profiles and varying levels of carbon market readiness as a result.

Sourced: Prepared by author

Caribbean ecosystems are critical as natural infrastructure supporting climate resilience and economic stability.

Aside from scattered areas of tropical rainforests and volcanic landscapes, much of the region’s natural assets lie in its marine ecosystems. The Caribbean contains an estimated 33–55% of the world’s seagrass, storing an estimated 1.3 gigatonnes of CO2 with a carbon value of nearly US$90 billion and broader ecosystem services worth US$255 billion annually. It is home to approximately 10% of the world’s coral reef ecosystems and expansive mangrove forests that sequester around 174 tonnes of CO₂ per square kilometre per year. A biodiversity hotspot, the region also houses over 1,000 marine mammal and fish species and more than 11,000 plant species, most of which are at risk of habitat loss and extinction.

These ecosystems anchor regional food security, coastal livelihoods, and tourism—the backbone of many of these island economies. The Caribbean is the most tourism-dependent region in the world, with 70% of its people living or working in coastal areas. As such, the region relies heavily on the strength and integrity of its ecosystems, which essentially function as a natural insurance mechanism.

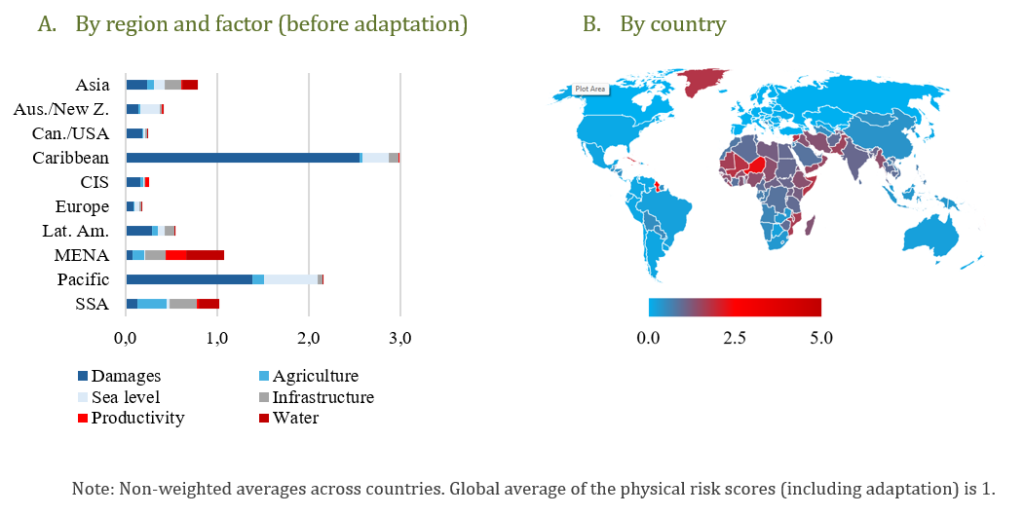

Located on a hurricane belt, the region is also simultaneously the most exposed globally to climate-related natural disasters, with physical climate risk indicators far outpacing other regions:

Climate Finance

Annual climate-related losses in the Caribbean have already reached US$12.5 billion and could rise to 10% of regional GDP by 2050 from sea level rise alone. The investment needed to mitigate these impacts is similarly staggering. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), more than US$100 billion is needed in adaptation investment for the entire region. In stark contrast, the Caribbean has been approved for upwards of US$800 million in international climate finance, largely in the form of grants and loans.

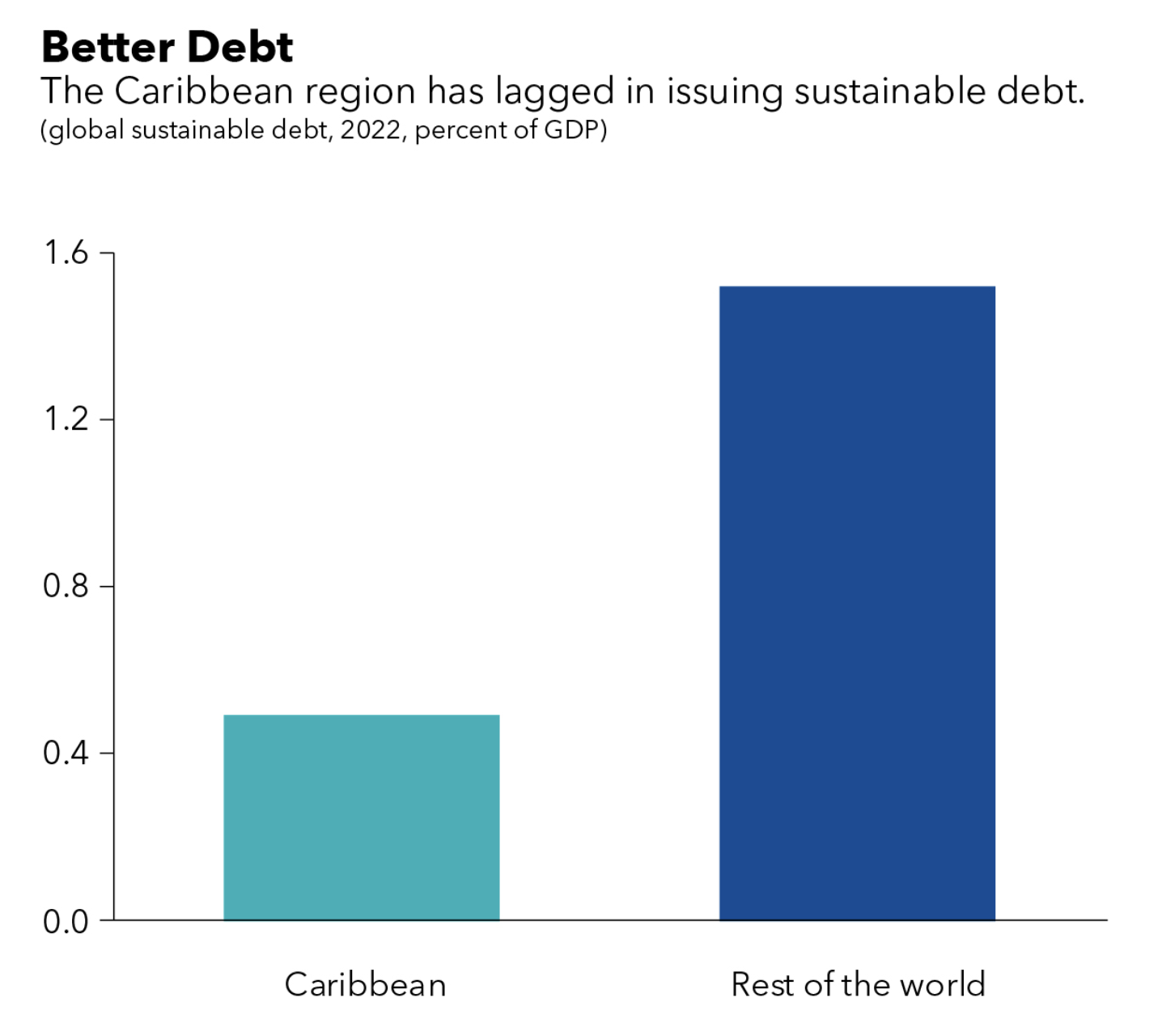

Beyond this, the region has made a name for itself in the climate finance space in its pursuit of alternative finance pathways, such as sustainable debt. Historically, the Caribbean has lagged behind in this area (see figure below), although there have been major milestones in recent years. Leading players like The Bahamas, Barbados and The Dominican Republic have unlocked hundreds of millions through debt-for-nature and debt-for-climate-resilience swaps and issuance of green bonds. COP30 also saw the launch of a Caribbean Multi-Guarantor Debt-for-Resilience Joint Initiative, aimed at boosting disaster preparedness while easing pressure on these debt-burden economies. Still, coverage levels remain far below the needs for rehabilitation and reconstruction as damages intensify.

Source: IMF

Otherwise, large-scale climate investment in the region has been relatively instance-driven, provided after the fact of destruction, as with Jamaica who recently received US$6.7 billion over a three-year period to support recovery after Hurricane Melissa caused damages of US$8.8 billion, roughly 40% of the country’s GDP, in October of this year.

Against this backdrop of urgent climate vulnerability, enormous adaptation needs, and a growing but still insufficient climate finance landscape, the Caribbean’s limited engagement in the global carbon market is particularly intriguing. Despite its wealth of natural assets and proven pursuit of and innovation in alternative climate finance mechanisms, the region remains largely absent from one of the most dynamic and rapidly expanding tools for mobilizing sustainable investment.

The State of Carbon Markets in the Caribbean

Most islands in the Caribbean have yet to integrate carbon market participation into broader development strategies. Activity in the voluntary market is negligible, with data available from Verra and Gold Standard suggesting less than 60 carbon projects active in the region.

None of the countries currently operate a carbon pricing or compliance mechanism, although the Dominican Republic has reportedly been exploring an emissions trading system (ETS) since 2020. Where carbon pricing does exist elsewhere, it is mostly implicit, using fuel excise taxes in economies dependent on imported fuel. In Jamaica, for example, about 79.6% of GHG emissions are subject to a positive net effective carbon rate (ECR) via these taxes, the highest in Latin America and the Caribbean combined.

There is no shortage of climate ambition in the region. In fact, many Caribbean nations are among the most ambitious globally in their climate commitments, pledging 100% renewable energy by 2030-2035, advanced land-use and ecosystem protection targets, and net zero targets by 2050 or earlier, even though the region accounts for only around 4% of global emissions.

Participation in carbon markets, however, remains the exception. Carbon market engagement in the Caribbean generally falls along three tiers of progress:

| Level of Participation | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Advanced / Active Architecture | Countries that have established legal and institutional frameworks or systems for carbon market participation, and/or have executed transactions. |

|

|

Emerging / Active Exploration |

Countries showing strong interest in Article 6 cooperation (i.e., exploring options, drafting policies, or preparing participation as part of net-zero strategies); some have already signed bilateral agreements. |

|

| Early-Stage / No Explicit Intent | Countries that have not signaled formal intent to participate but acknowledge carbon market opportunities, usually in the reporting of their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), without further concrete action. |

|

The implications of the region’s relative dormancy are up for debate. In the context of today’s evolution of carbon trading into a foundational asset of the global transition to net zero, Caribbean nations stand to miss opportunities for new revenue streams and direct investment opportunities for sustainable systems and infrastructure that are otherwise being pursued through traditional financing methods. Increasingly exposed to hurricanes, sea-level rise, and water scarcity, islands are left dependent on foreign aid or debt-financed projects for building resilience capacity. Furthermore, considering the underlying reality of carbon markets as geopolitical and strategic instruments, limited participation risks marginalization and undervaluation in negotiations around carbon mechanisms, essentially pricing the region out of influence in a market that, save for existing power dynamics and inequities, continues to shape who benefits from global decarbonization.

Recent developments suggest there might be a ripple in the tide. In 2024, the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) launched a study into the region’s blue carbon assets for purposes of guiding future market participation. Additionally, capacity building initiatives around a regional market such as the Global Carbon Market (GCM) project, launched by GIZ on behalf of Germany’s Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action (BMWK) in 2021, had started to lay the groundwork for a regional alliance on carbon markets and climate finance.

Still, tangible outcomes have yet to be realized. And in a world where carbon markets are rapidly reshaping how climate action is funded, the cost of it is becoming increasingly difficult to ignore.

Understanding this silence is the first step toward addressing it. In the next installment of this series, we turn to the core question: why does a region with unparalleled climate exposure and meaningful natural capital remain on the margins of a market uniquely positioned to support them?